Civic Engagement Reports

Discover OSUN Civic Initiatives

CONTACT US Open Educational Resource (OER) Open Society University Network Website: Opensocietyuniversitynetwork.org

ENGAGED CITIZENSHIP

Creating A Student Civic Engagement Project Database

VISUALIZING REPORT

A MISSION REALIZED

OSUN’s mission is to prepare students from diverse geographies and backgrounds, through rigorous liberal arts and sciences education, to address global challenges as thoughtful and engaged citizens. It advances global learning, promotes academic freedom, and expands access to higher education.

325

Projects Funded

Number of civic engagement projects supported through targeted micro-grants by OSUN institutions.

280

Student Participants

Count of students actively involved in creating and executing community impact projects.

450

Institutions Engaged

Total OSUN-affiliated institutions that developed initiatives utilizing awarded micro-grants.

TABLE OF CONTENT

- About Open Educational Resource (OER)

- About Civic engagement courses

- Student projects across OSUN institutions

- OER analysis

- Skill development

- Course evaluation

- Case study introduction

- Coaching Teens for Social Inclusion

- Weshwa_Be Empowered

- EJAAD Berlin

- Theatre of the Oppressed

ABOUT OPEN EDUCATIONAL RESOURCE (OER)

This report details how OSUN-affiliated projects utilize micro-grants to enhance community participation, create solutions, and foster sustainable development.

Given the uncertain nature of contemporary times and the increasing number and intensity of attacks on democracy worldwide, the Open Society University Network (OSUN) has rightly made civic engagement one of the most influential and integral components of its educational offerings. Over the past four years, nearly 50 Civic Engagement courses have been taught across the network, enrolling more than 800 students. OSUN has also developed a Certificate in Civic Engagement, which has been completed by over 300 students. Additionally, around 120 Civic Engagement Fellows have supported their universities in planning and delivering civic engagement activities. Their work has impacted thousands of people and communities across the world, showing how powerful the network could be for global civic transformation.

For many OSUN member institutions, equipping students with the skills and opportunities to engage with their communities and drive positive change is a core part of their mission. This commitment is reflected in student projects undertaken as part of graduation requirements or community outreach initiatives across the network. Civic engagement courses emphasize the practical side of engaging with one’s community: alongside gaining theoretical knowledge, students are asked to design projects that address crucial community needs. Students have developed a wide variety of project proposals: some of them, often supported by OSUN funding, have been implemented and have had meaningful social impact. In this manner, students come to understand the extent that theory and practice are interrelated mutually helping, shaping them into intelligent and capable public servants.

The present research project offers a snapshot of the work students have accomplished to date through their projects. Using a combination of qualitative, such as interviews and questionnaires, and quantitative methods, we provide a summary of the skills students developed during their OSUN courses that supported them in conceiving, planning, and, in some cases, implementing their projects. We were also able to identify key challenges students faced, the lessons they learned and the types of skills essential to reaching their goals. As part of this research, we were also able to collaborate with 8 students and put together case studies based on their experience. We hope these case studies will serve both as examples of the kinds of achievements students can attain and as practical guidance for future cohorts working on projects in the civil society space.

I would like to thank OSUN who provided the opportunity and funding to complete this important research initiative under OSUN’s Open Educational Resource proposal call. Also, many thanks to the team that worked hard and put together this project.

Project Leaders:

Dr. Chrys Margaritidis – Dean of International Initiatives, Director of Institute for Intern. Liberal Education/Bard Abroad, Bard College

Brian Mateo – Deputy Director of Programs and Partnerships, Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs

Project Consultant:

Erin Cannan – Vice President for Civic Engagement, Bard College

Project Manager:

Zarlasht Sarmast – Network Coordinator, Open Society University Network and Business Manager, Bard NYC

Project Assistants:

Aaron Dickinson – Bard College

Myat Moe Kywe – Parami University

Abdullah Naseer – Bard College Berlin

Huy Vu – European School of Management and Technology (ESMT Berlin)

Dr. Chrys Margaritidis

ABOUT CIVIC ENGAGEMENT COURSES

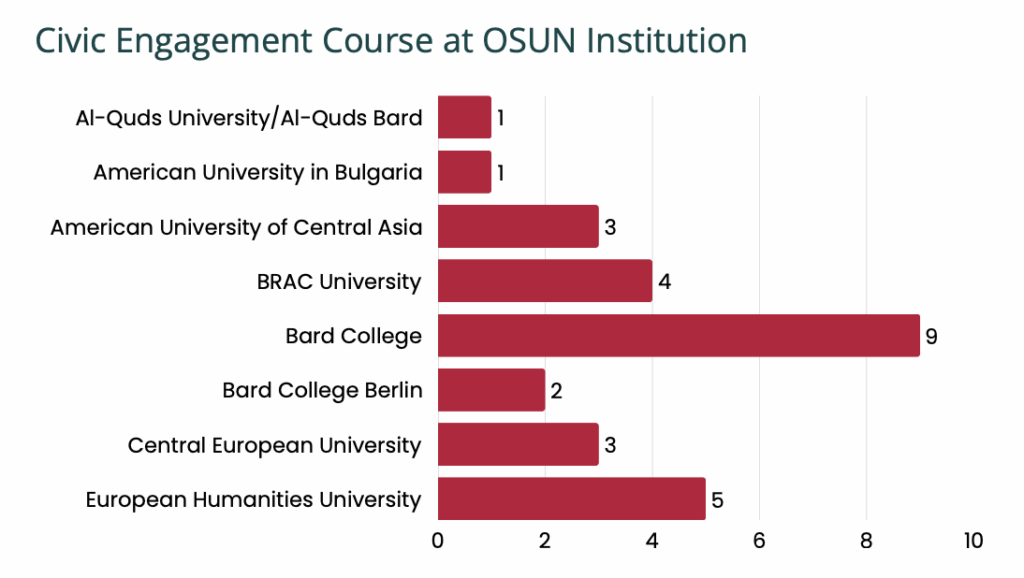

The quantitative observation reveals a significant disparity in course offerings among institutions. Bard College leads by a substantial margin with 9 courses, indicating a strong focus on civic engagement within its curriculum or a broader program scope compared to other institutions. The remaining institutions, with course counts ranging from 1 to 5, demonstrate a moderate commitment to civic engagement courses.

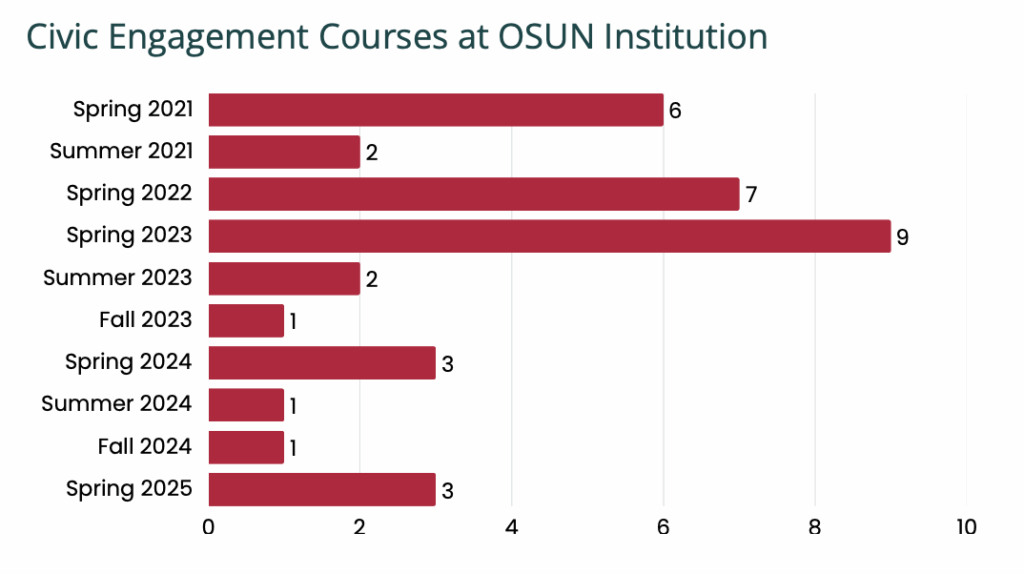

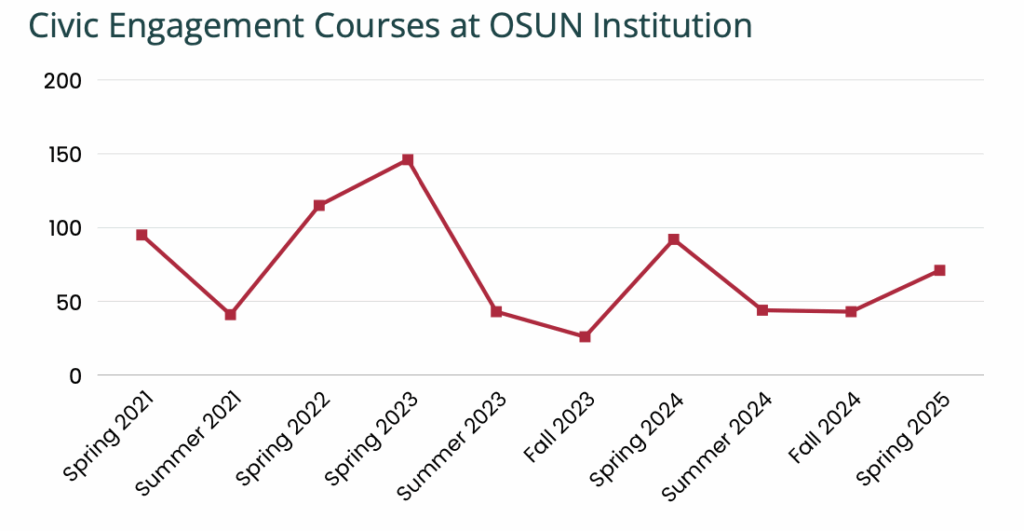

Spring terms clearly drive the program’s momentum, climbing from six courses in 2021 up to a high of nine in 2023 before settling back to three by 2025. Summers act as a light supplement—offering only one or two courses in select years—while fall courses have only appeared as one-course pilots in 2023 and 2024. The pattern suggests a focus on building spring capacity first, with cautious forays into out-of-peak semesters to test demand without overcommitting resources.

Spring enrollments rose from 95 in 2021 to a peak of 146 in Spring 2023, reflecting strong year-over-year growth as more courses was offered. Summer and fall courses steadily attracted around 40+ students, demonstrating consistent off-peak engagement.

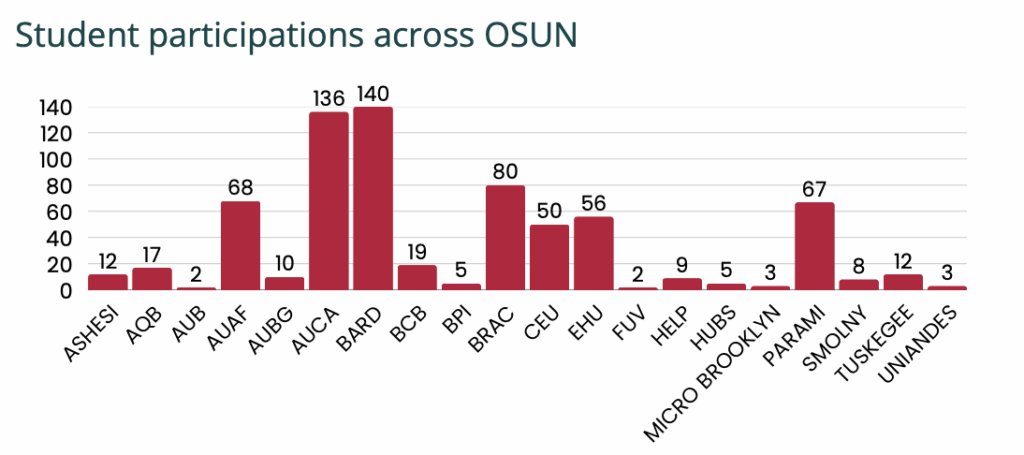

Bard College and AUCA have the highest students enrollment across Civic Engagement Courses, while other institutions, such as BRAC University, AUBG, Parami University, AUAF, EHU, CEU have moderate students enrollment. The remaining institutions have few enrolled students.

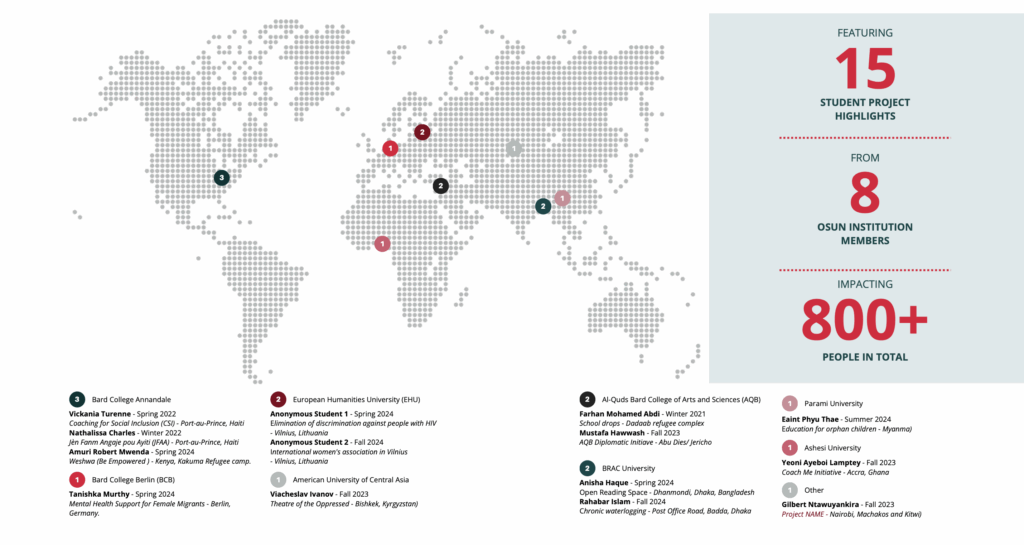

STUDENTS PROJECTS ACROSS OSUN INSITUTIONS

Common Goals from Students

As encouraged by the course, all projects were based in community and community engagement. Most projects involved education rather than a specific call to action. The most common form this education took was a workshop or a series of classes focused on a specific problem that requires more awareness in the community. In addition to educating a broader community, many projects focused on specific groups. For several projects this meant raising awareness among college age students. For other projects, the focus was on younger students who project leaders identified as lacking key skills, necessary education, or civic awareness.

Empowerment & Capacity

Building

All projects focus on empowering marginalized groups—whether women, youth, migrants, or people with disabilities—by developing practical skills and personal growth to increase their independence and community leadership.

Inclusion and Social

Awareness

A key emphasis is on promoting social inclusion and raising awareness to combat stigma and inequality, ensuring that diverse populations have equal opportunities to participate fully in society.

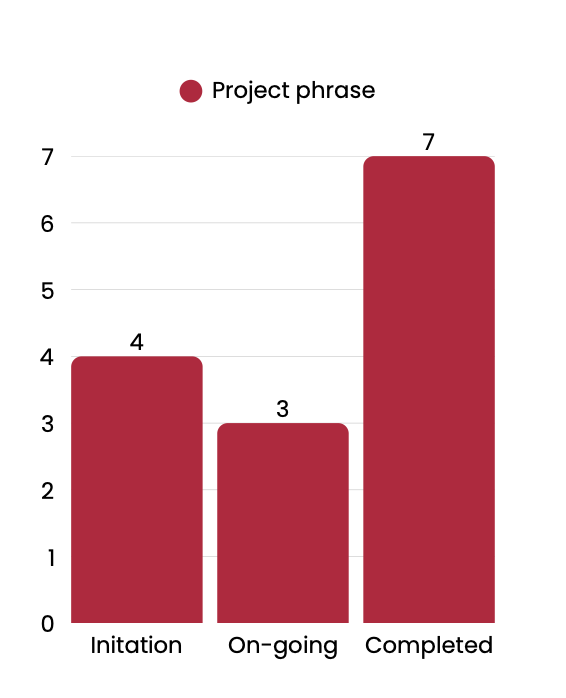

Project Implementation

10 out of the 14 projects were implemented. 7 projects have been completed and 3 are still ongoing as they were designed to continue serving their communities. The discrepancy comes from one project leader who used the skills acquired in the course to focus on a project that was very different from the one proposed at the end of the course

Impact Commonalities

All projects aimed to connect members of a community to information and resources that were unavailable or hard to access prior to the project’s implementation. The most common way for the community to interface with the project was from workshops or sessions that brought multiple people together at the same time to discuss the same issue. Many projects also offered an online component for advertising, more information, or over the internet participation in workshops.

Similar Barriers Faced

The most common reported barrier to project completion was budget. Several projects were able to receive funding or micro-grants from one or more sources outside of OSUN. Some projects were able to find financial support from OSUN. All but two projects that did not receive any support were not implemented. Most of the projects that were based on the African continent were unable to find a funding source

Another common barrier was safety. Violent crime or lawlessness coincided with some of the communities addressed in the projects. The concern for safety has stopped the implementation of one project and diminished the ability for another project to operate in person.

SKILL DEVELOPMENT

Leadership and Teamwork

Students gained skills in leading diverse teams, encouraging participation, sharing a common vision, and managing group dynamics across cultural contexts.

Project Planning and

Implementation

Tools like mind mapping, SMART goals, and community mapping helped students plan projects clearly, identify resources, and execute their plans effectively.

Critical Reflection on

Positionality

They learned to recognize their own positionality—understanding how their background influences their perspective—and how to engage communities respectfully.

Communication and

Intercultural Understanding

Students improved their ability to communicate and collaborate with people from different backgrounds, including managing conflicts and respecting cultural boundaries.

Problem-Solving and Conflict

Resolution

Students developed skills to observe community issues, facilitate dialogue, and mediate conflicts to create inclusive and peaceful environments.

KEY IMPACT PATTERNS

Capacity Building and

Empowerment

All projects emphasized equipping participants with practical skills— whether leadership, economic, or civic—resulting in increased confidence and ability to take action in their communities.

Community Trust and

Engagement

Building trust was fundamental, overcoming initial skepticism to foster participation, open communication, and a shared sense of ownership among diverse community members

Collaborative Networks and

Sustainability

Strong partnerships with local leaders, organizations, and peers created support systems that enhanced project legitimacy and helped sustain positive outcomes beyond the project timelines,

PROJECT SUSTAINABILITY

Students expressed a strong desire to continue their projects, highlighting the importance of ongoing efforts and community impact. However, they identified financial limitations as the primary barrier to sustainability. In addition to funding, students emphasized the need for strengthening team capacity and expanding human resources to effectively manage and scale their initiatives. These factors are critical to ensuring the long-term success and growth of their projects.

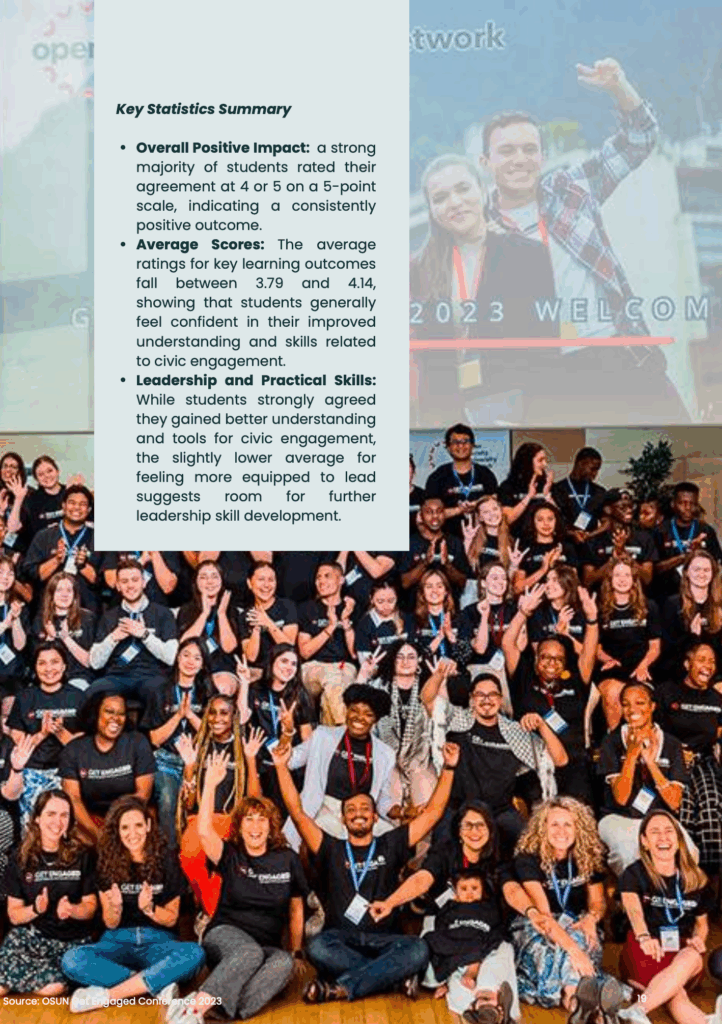

COURSE EVALUATION

1. Taking OSUN course with other students improved my understanding of Civic Engagement

The feedback shows that the majority of students (86%) felt that taking the Civic Engagement course with students from around the world enhanced their learning of the subject matter, with an average score of 4.14 out of 5. While most students were highly positive, one low score suggests an opportunity to learn more about individual student experiences.

Source: OSUN Get Engaged Conference 2024

2. I am more equipped to lead in my community as a result of taking this course.

Most students (78%) agreed or strongly agreed that they feel more equipped to lead in their communities as a result of this course, with an average score of 3.79 out of 5.

3. I have a better understanding on how to use civic engagement practices to make positive change in my community.

The feedback shows that the majority of students (86%) felt that the course helped them gain a better understanding of how to use civic engagement practices to make positive change in their communities, with an average score of 4.14 out of 5.

4. After taking the course, I am better equipped to work with community members to build civic engagement initiatives.

The feedback shows that the majority of students (79%) felt better equipped to work with community members to build civic engagement initiatives after taking the course, with an average score of 4.07 out of 5. While most students responded positively, one low score suggests an opportunity to understand individual challenges more deeply.

5. After taking the course, I have a better understanding of core notions of citizenship and power and their connection to civic engagement.

The feedback shows that the vast majority of students (93%) believe the course improved their understanding of citizenship, power, and their link to civic engagement, with an average rating of 4.0 out of 5.

6. After taking this course, I have a better understanding of the contexts civic engagement takes place in – at different levels (local, national, global) and between/across state and non-state organizations/ groups, as well as in countries with different levels of political, socioeconomic development and diversities of population.

On a scale of 5, the average score of 3.93 reflects that most students feel they have improved their understanding of the diverse contexts in which civic engagement occurs— across local, national, and global levels, involving both state and non-state actors, and within countries of varying political and socioeconomic conditions. Approximately 93% of students rated their understanding at 4 or above, indicating a largely positive response

CASE STUDY INTRODUCTION

Since 2021, the OSUN Civic Engagement and Social Action Courses have welcomed students from around the world. Almost two hundred participants from different institutions across the world have completed the course and gone on to launch community initiatives. OSUN Civic Engagement and Social Action courses equip students with the tools, knowledge, and confidence to drive meaningful change in their communities while also strengthening global understanding to maximize the local impact. One of the most important elements of civic engagement is reflection; understanding what worked, what did not, and where to improve. With this in mind, this OER Project aims to examine how well the goal of OSUN Civic Engagement and Social Action is being achieved. To do so, we reached out to alumni of the course and invited them to reflect on their journey during and after the course. This work is a collection of case studies that reflect the students’ experiences taking the course, the projects they developed, and the challenges they encountered while turning their project ideas into action.

The civic engagement initiatives led by students we interviewed .

address a wide range of issues rooted in their local contexts. While the issues appear different, the core strategy students take to address these issues lies around education and advocacy. For instance, there are social initiatives aimed to change the perceptions of the communities from social stigma, inequality, and gender taboos. Despite the differences in project’s focus, education and advocacy were found to be the key strategies students used to drive change. For example, several initiatives used education to change harmful community perceptions by creating safe spaces for dialogue and awareness. Others focused on providing practical skills, training programs, and workshops to empower individuals who often lack access to such opportunities.

When asked the students to reflect on their learning journey with the OSUN course, the student leaders shared a similar takeaway from the course: leadership. Interestingly, although the definition of leadership has not yet earned universal definition, OSUN students shared a common understanding, which is centered around “community and getting people involved.” Student leaders of the projects featured in this work describe leadership as the ability to inspire people to join their causes and motivate them to work towards the shared goals. ‘Getting people involved in the project needs leadership skills and that is what the OSUN course offers for us,’ the students answered. As students reflected, leadership is not only about guiding a team, it is also about forging strong relationships with community members and creating a shared sense of purpose. Many pointed to the course as their first opportunity to understand how to identify potential allies, map out resources, and build partnerships, lessons that proved essential when they began implementing their projects.

The journey from theory to practice was not without its challenges. A major obstacle many students encountered was the lack of resources to implement their original project plans. This gap between classroom concepts and on-the-ground realities pushed students to rethink feasibility, adapt their goals, and, in many cases, revise their approaches based on feedback from the communities they hoped to serve. Flexibility emerged as a key success factor

allowing students to adjust their strategies and ensure their initiatives remained relevant and achievable. The successes also came from preparation, especially when students paired their work to the specific needs and concerns of their local communities. The OSUN course’s emphasis on the specific steps a project must take towards implementation as well as conscious exploration of participants’ perspective and positionality were cited as ways in which students felt prepared to take on the challenge of leading a project. Another challenge was keeping momentum of the project, especially in motivating team members and sustaining community engagement. Students often struggled with how to maintain interest and ensure consistent participation. Many expressed a strong desire to further develop the skills to involve and inspire others, as they came to see this as a core part of sustaining any long-term initiative.

COACHING TEENS FOR SOCIAL INCLUSION

By Vickania Turenne – Bard College Annandale

Small Hope During Difficult Times

In the fall of 2022, Vickania Turenne, a student from Bard College Annandale, felt inspired to launch a community-based initiative in her home country of Haiti after taking the OSUN Civic Engagement and Social Action course. Haiti is ranked as one of the countries that has the highest crime rates in the world and has become worse after 2021 due to political instability and a lack of effective governance. During this difficult time, she became more concerned about the teenagers who are often overlooked in crisis responses, despite being prone to exposure to violence, and vulnerable to involvement in delinquency. Vickania became concerned about the fate of these communities and felt compelled to take action. Out of this concern, she developed a project titled “Coaching Teens for Social Inclusion.” She initiated the project to raise awareness about the treatment of underprivileged children in Haiti and to educate the teens to help them develop themselves and avoid falling into juvenile delinquency through child rights, cultural identity and peace building conferences. Moreover, the project was designed to create self-esteem training and recreational activities such as handicraft workshops.

Adjusting Plans as A Strategy in Successful Community Work

Originally, Coaching Teens for Social Inclusion aimed to support children aged 10 to 16 from disadvantaged backgrounds, such as those living in orphanages, raised in single-parent households, or experiencing

homelessness. Vickania recognized that these children face significant socio-economic challenges and inequality, making them more susceptible to involvement in delinquent behavior or become victims of the rising crimes. When underprivileged children face these risks, they are often treated differently within their communities, reinforcing cycles of marginalization and exclusion.

However, despite her initial plan, Vickania faced limitations when trying to implement the project as originally proposed in her OSUN Course on Civic Engagement and Social Action. She lacked the professional training and capacity required to work with children who may have experienced severe trauma. Recognizing this gap, she decided to pivot her focus to another vulnerable group; people with disability, specifically the deaf community. As she is an experienced sign-language interpreter, she felt it was more feasible to connect with the community and support them. This revised targeted population of the project maintained the core mission of social inclusion, but it honed in specifically on the mental health needs of individuals with hearing impairments. Vickania observed that deaf people are often left out of conversations about violence. And, there is a common but a misinterpreted assumption that their inability to hear gunshots is a valid reason that they could not have equally experienced the similar mental distress in violence. In reality, she found that many deaf individuals suffer in silence, carrying the weight of their experiences without having a support system. They may not hear the violence, but they see its impact on their families, sense the fear in their communities, and face additional barriers when trying to express their distress.

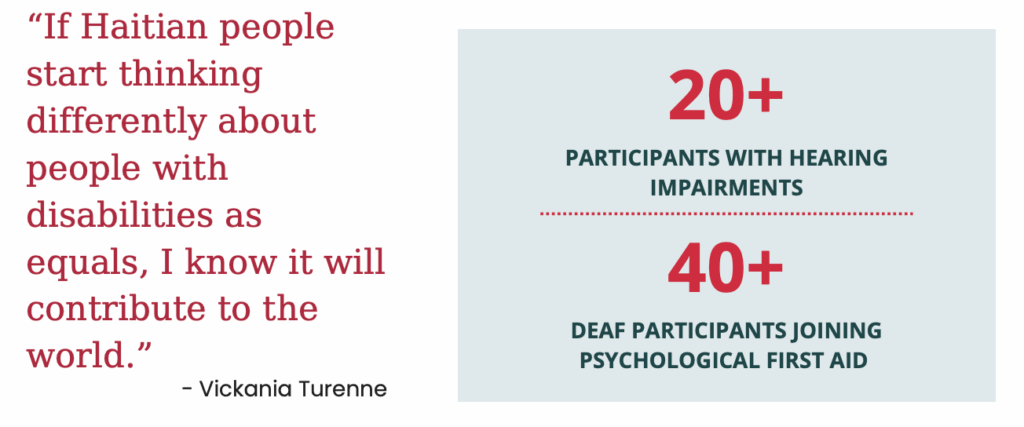

Through her project, she was able to provide two mental health support activities for 20 individuals with hearing impairments and offered psychological first aid to 40 more deaf participants. The sessions focused on helping participants process trauma and build resilience in an environment where violence is constant. One impactful moment came when a woman, who had never even heard of the concept of mental health, finally found a safe space to express her trauma and seek professional help, a moment Vickania described as truly meaningful.

Fueling Passion and Capacity with OSUN for Change

Vickania thanks the OSUN Civic Engagement and Social Action Course for equipping her with the knowledge, tools, and confidence to launch her initiative. Throughout the course, she gained four essential competencies: leadership, project management, intercultural communication, and teamwork. Most importantly, she developed a deeper understanding of what it means to be a global citizen to be able to see local issues as part of a broader, interconnected world.

Breakout sessions during the OSUN course allowed her to connect with students from different countries and contexts, many of whom were also designing impactful civic engagement projects. These peer discussions inspired her to act and empowered her that she was not alone. Course lessons such as mind mapping and stakeholder mapping stood out for her in identifying the community needs and the support she needed to start her initiative. She also emphasized how the course taught her the value of clear communication, skills that were practically useful when she engaged with a diverse range of stakeholders in her project, from community elders to school leaders to members of the deaf community. The concept of global citizenship taught in class helped her view the treatment of people with disabilities not just as a Haitian issue, but as part of a global struggle for equality and inclusion. As she put it, “If Haitian people start thinking differently about people with disabilities as equals, I know it will contribute to the world.”

Overcoming Roadblocks for Impact

Similar to other civic initiatives, Coaching for Social Inclusion was not without its challenges. One of the first obstacles Vickania faced was finding the team who shared her vision and were willing to work with the deaf community. This is where the stakeholder mapping exercise from the OSUN course proved invaluable as she said. It helped her identify potential allies and build a network of support around the project. Because of having the right partners, she was able to secure a venue for free of charge by partnering with local schools who were willing to support her cause.

Another major challenge was the lack of resources. As Vickania pointed out, resources were not all about money and grants. It was also about skilled trainers, volunteers, and local partners. At times, the lack of these important supports made the project feel daunting. But she recalled a phrase her classmates during the OSUN course repeatedly shared: “If not now, when?” This mindset pushed her to start with small things. Therefore, to get the project off the ground, she used her own money and reached out to community partners for further support. Over time, these small steps set the momentum of her project. Through this process, she learned a valuable lesson that it’s possible to start meaningful community work without having everything in place at the beginning. As she reflected, commitment and courage often matter more than having everything in place.

One of the project’s most rewarding successes for Vickania was the trust she built within the deaf community. Initially, many participants were hesitant or skeptical to participate in the activities. But over time, the sincerity and impact of the work became clear. Participants engaged actively, and many expressed how much they appreciated having a space to be seen and heard. For Vickania, the most powerful moment came when a deaf woman, previously unaware of what mental health even meant, opened up to a therapist and began her journey toward healing from the neglect of her own psychological needs.

Visualizing the Future of Coaching for Social Inclusion

Looking ahead, Vickania hopes to expand Coaching for Social Inclusion by actively involving youth in promoting more inclusive attitudes toward people with disabilities. She believes young people can become agents of change, and she wants to equip them with the tools to do so. The next phase of the project will include training sessions for youth from local associations, schools, and churches. Her goal is to challenge traditional perceptions towards people with disabilities and create a community where people with disabilities are seen and treated as equals. To achieve this, she acknowledges the need for more strategic outreach, especially to youths who may not be interested in disability inclusion. Another key important element of her project is about safety, given the ongoing violence in Haiti. Creating safe spaces where community activities can take place is a priority moving forward.

Moving on, Vickania is hoping to garner support from all possible stakeholders to expand the project’s impact, and reach to those who need it most. Her story is an example of what can happen when young leaders step up to serve their communities with vision, adaptability, and heart.

WESHWA_BE EMPOWEREDBuilding – Economic Resilience of Women in Kakuma Refugee Camps, Kenya

By Amuri Robert Mwenda – Bard College Annandale

Reapproaching the Same Old Issue in Kakuma Camps

During the 2024 Spring Semester, Amuri Robert Mwenda proposed a community project named Weshwa_Be Empowered as a part of OSUN Civic Engagement and Social Action Course. In Kakuma refugee camps, many women are the primary breadwinners of their families. Yet, they receive limited support to overcome the systematic barriers such as restricted access to employment opportunities, and insufficient availability of financial capital. Even when other INGOs and NGOs provide grants to support these women in the camps, many of them are one-time offers. When the grant recipients lack essential skills and knowledge to start their businesses sustainably, the cycle is repeated for them back to poverty. Robert observed this gap in his community and wanted to do something to change the situation. This is why Robert developed a community initiative to support these women in the camp in a more sustainable way different from the traditional approach of giving a one- time grant. Rather than giving away the money to the women as a charity, he initiated a sustainable model that provides the learning opportunity for capacity development and repayable financial capital loans. From this project, Robert aims to improve the sustainable livelihoods of women living in the Kakuma Refugee Camp in Kenya where he grew up. Robert highlighted that OSUN Civic Engagement and Social Action Course provided him the foundational structure and knowledge to design the project.

Building Sustainable Livelihoods of Refugee Women in the

Camp

Weshwa_Be Empowered is a community-driven project designed to promote sustainable livelihoods among women in Kakuma Refugee Camp by equipping them with entrepreneurial skills and providing access to financial capital. The project targets women from Kakuma Refugee Camps who are willing to start or grow their own businesses but face structural barriers such as poverty, gender inequality, and lack of access to necessary skills-building training. Currently, 25 women from the camp have been recruited and trained with capacity-building workshops on important topics such as financial literacy, bookkeeping, business planning, and entrepreneurship. After the training, 10 women were selected to receive interest-free micro-loans, and they can repay the loans within a year. Unlike traditional models that provide one-off grants, Robert chose a loan-based model. He said: “This is a strategic approach to promote ownership, and motivate the loan recipients’ women to work well in their businesses.” At the same time, this approach can make the project financially sustainable over the long-term. The goal was not only to help women launch small businesses but also to provide opportunities to develop the skills and confidence needed for long-term self-reliance. By combining financial access with practical training, Weshwa_Be Empowered offers a supportive environment for women to lead their own paths out of poverty and contribute meaningfully to the economy of Kakuma and Kenya more broadly.

How OSUN helped Robert for His Community Vision

Robert thanks the OSUN Civic Engagement and Social Action Course, for equipping him with practical knowledge and skills such as community mapping, leadership, communication, conflict resolution, and SMART goal setting. Through this course, he learned that leadership in community work is not about imposing solutions based on what he thinks is right but about engaging with the community to identify root causes together with the community. Only after that, it was possible to collaborate on solutions that reflect and address the needs of the communities. The community mapping exercises taught him how to listen deeply and understand the lived realities of the people he hoped to serve. He also applied SMART goals to design activities to organize a project with clear timeline and objectives. In addition, foundational knowledge he learnt about monitoring and evaluation (M&E) during the course was said to be applicable in selecting loan recipients and measuring the project’s progress. Furthermore, conflict resolution skills also helped him navigate difficult situations within the community and listen actively to concerns raised by both stakeholders and community members.

Setbacks in Action and Strategies in Focus

Robert shared the challenges he had to first-hand encounter during the execution of the project’s idea proposed in class on real ground. One of the first obstacles was the lack of both financial and human resources. Reaching out to organizations or partners to support a new initiative was extremely difficult, especially in Kakuma where several similar projects have already existed in the community run by different organizations. Trust was a pressing concern because community leaders and beneficiaries were critical about the project’s idea, unsure if this would be another one-time intervention. In addition to external partnership building, the internal struggle was to gain confidence from the targeted community members. When Robert contacted and talked to women in the camps about their situation and what support they require, they were initially hesitant to share, probably due to the fear or uncertainty of the intention of the project.

Applying what he learned from the OSUN course, Robert overcame these barriers through strategic community engagement, collaborative planning with local community leaders, and identifying external mentors who provided support in areas of expertise. When asked about the important highlights of the project, Robert shared the story of a woman who lost her husband and faced financial struggle to self-sustain herself. After joining the program, she gained necessary skills training and

financial loans to initiate a small grocery business. Few months later, the woman started doing well in her business and generated stable income, even being able to repay the loan. Her ability to repay the loan and sustain her business became a powerful success story that built credibility and encouraged others in the camp to participate.

Imaging the Next Phase of Weshwa_Be Empowerd

Robert is now preparing to expand Weshwa_Be Empowered with better opportunities and more community members. He wants to reach more women in Kakuma, especially those who face extra challenges, such as single mothers, young women, and people with disabilities. As part of the next phase, he plans to integrate vocational training such as tailoring, soap-making, and handicrafts, based on what women are interested in and what is needed in the local market. These practical skills will build on the financial and business training already offered, helping women create products and services they can sell. Robert also plans to improve how the project tracks its progress by creating a clear monitoring and evaluation (M&E) system. This will help him understand what is working and make evidence-based modifications based on feedback from the participants. Building stronger partnerships is another priority because Robert wants to work more closely with local NGOs, private companies, and community groups for support, mentorship, and funding. To grow the project successfully, Robert stressed the need for more development opportunities and guidance from experienced mentors for him and his team, especially in areas like project management, writing grant proposals, and working with different partners. The next step is a mid-term evaluation, which will help guide updates to the project’s plans towards the realization of the whole project. In the future, Robert hopes Weshwa_Be Empowered can grow into a larger community center that supports refugee-led solutions and empowers women to lead change in Kakuma and Kenya.

EJAAD BERLIN

By Taniska Murthy – Bard College Berlin

The Initial Project Proposal

Taniska Murthy is a student at Bard College Berlin and took the OSUN Civic Engagement course in Spring 2024. For the course, Tanishka proposed a project that sought to tackle the experience of female migrants in Berlin and specifically the mental health support that they were receiving. The project planned to include a session with migrants to hear their experiences. The project would then involve research based events to eventually produce an academic and specific policy proposal to give to local officials.

Expanding EJAAD to Berlin took time and attention away from the mental health focused project, so that project was never implemented. Taniska’s experience with the course did end up impacting EJAAD Berlin in a variety of ways.

What is EJAAD Berlin?

The name “Ejaad” comes from the Dari word for creativity. EJAAD was started in Japan and founded by a mentor of Tanishka’s. That is where Tanishka first got involved with the project. As an NGO, EJAAD facilitates the sale of embroidery made by women in Kabul, Afghanistan to sell internationally. This provides the women who make the jewelry/embroidery with a stable income and a higher level of empowerment. Over the course of EJAAD’s existence, the funds have led to the creation of a health center and a learning center in Afghanistan. After being involved with the project for several years in Japan, Tanishka decided to create a chapter of EJAAD where she was studying in Berlin.

Today, chapters of EJAAD exist in America, China, and Japan. In a Berlin context, Tanishka asked Afghan students if they would be comfortable with a chapter of EJAAD in Berlin being started at BCB. For EJAAD chapters in America, China, and Japan, embroidery is sold and the money is sent back to the women who are sponsored by the organization. In Berlin that was not feasible, so an outreach program for education and crowd funding was decided on as the foundation of the Berlin chapter of EJAAD. Over the past year, the Berlin chapter of EJAAD has hosted film screenings (Breadwinner), collaborated with women’s groups on the Bard Berlin Campus on international women’s day, and held speaking events with activists. With an average of 15 people attending each event, EJAAD Berlin boasts a higher attendance record than most student run organizations at BCB.

Future Plans for the Project

In the future, EJAAD Berlin plans on hosting a women’s health event. There are also plans to increase the number of grants the Berlin chapter has access to.

Tanishka intends on studying abroad for a semester and has already made plans for how that can be achieved while also organizing EJAAD Berlin and setting the chapter up for success and longevity. This is possible because EJAAD’s collaborations come from abroad or on campus and events are often hosted online. By delegating students between individual tasks versus collaborative tasks, Tanishka is confident in her peers involved in the organization. As new students get involved and eventually leave Berlin for home or abroad, Tanishka predicts that she or others in the organization will go on to found more chapters of EJAAD.

Tanishka’s Experience with the Civic Engagement Course

For Tanishka, learning about positionality was one of the most important aspects of the Civic Engagement Course. She says that positionality is something “We have this at the back of our heads, where it is assumed that we should know cultural boundaries.” It can be hard not knowing what one simply does not know. Taniska found that the course greatly emphasized on students looking at their own positionality. “It helped me realize that if you care about a project, you have to know that communities aren’t made uncomfortable or not respected by the project. That gets you more support from diverse communities.”

Positionality was reinforced when the course took students on a Berlin Lab tour. This tour was based on a decolonial understanding of the city of Berlin

and how the city itself interacted with various communities throughout history. This helped Tanishka be cognizant of how projects would be received. By knowing more about her local community, Tanishka was better able to understand what that community could most benefit from and what obstacles would exist to a hypothetical future project.

This ties into the teamwork component of the course. Tanishka said that “it helped to discuss with others from other cultural contexts. European students and non-European students could discuss what makes sense in Berlin versus somewhere else.” Perspectives from students from America, Europe, Asia, and locally in Berlin allowed discussions of what projects could work at BCB and how they would differ from projects based in students’ home communities.

When asked about her final takeaways from the course, Tanishka stressed that positionality most impacted her understanding of her work. She also mentioned that the instruction given on interviewing skills was very helpful and that she “wouldn’t get those communication skills elsewhere.”

How the Course Impacted EJAAD: Positionality and

Collaboration

Tanishka’s work with EJAAD Berlin was influenced by her experiences with the Civic Engagement Course. By starting slowly and involving Afghan students in the conceptual components of what would become EJAAD

Source: EJAAD Berlin x Afghanistan Activist Collective (2025)

Berlin, Tanishka focused on positionality as she started her project. She considered how the project would be received and made sure that communication was done right.This included understanding what events would be the most successful on campus. As BCB has a large arts program, the movie screening was the most attended event and has become a model for future EJAAD Berlin outreach.

Just as the course brought new information and cultural understanding to Tanishka, she aims for EJAAD Berlin to inform the BCB community on the communities that EJAAD is involved with. The EJAAD Berlin events included many guest speakers. EJAAD Berlin has collaborated with Little Sun, a Berlin based company that sent a representative to talk about milk production in Zambia in a sustainability focused event; Shreya Patel a Canadian/Indian actor who spoke to attendees of an EJAAD event; a Rotterdam professor held a talk on menstrual health in the global south; a radio show in Afghanistan talked about how they educated girls through radio and television; finally, Pashtana Durani, founder of LEARN Afghanistan spoke “from a place of care and knowing about the issue” to students who wanted to hear about her experiences.

Founding EJAAD Berlin and hosting these events required dedication and patience on Tanishka’s part. By combining her own experiences with those of her peers through positionality and teamwork, Tanishka has so far made EJAAD Berlin a success.

THEATRE OF THE OPPRESSED

By Viacheslav Ivanov – American University of Central Asia (AUCA)

How the Project Began

Viacheslav Ivanov took the OSUN Civic Engagement Course in the Fall semester of 2023 at the American University of Central Asia. As the final assignment for the course, Viacheslav proposed a series of theatre based workshops in Bishkek that would be learning based experiences that challenged gender inequality and stereotypes. The initial project proposed many involved performances and workshops in Bishkek. The realized version of the project reduced the number of workshops but increased the geographic scope and reach of the project by including several Kyrgyz towns and cities as well as a workshop in Kazakhstan.

Putting on the Show(s)

Viacheslav identified that stereotypes, especially gendered stereotypes, were still prevalent in Kyrgyz society. The resulting gender inequality through biases and treatment keep Kyrgyzstan from being an equal society. His project focused on diminishing those stereotypes.

Viachelsav’s workshop based project was called the “Theatre of the Oppressed.” Its goal was to contour the different gender stereotypes among the participants in an interactive theatre form. By using the medium of participatory theatre, the audience engaged with the story and changed how the performance unfolded. The first performance in Bishkek Kyrgyzstan focused on gendered stereotypes common in Kyrgyz society at large. (Such as the prevailing stereotype that certain jobs or careers are necessarily gendered). The second performance was focused on gendered stereotypes in a university setting. (Such as the stereotypes that encourage a culture of harassment on college campuses).

In the workshops, the participants and the actors were both women and men. The biases of the audience would be challenged through the actors’ portrayal of scenarios in which a stereotype caused harm. After actively engaging with the performance in a learning based experience, the audience was led through a discussion. Questions such as: ‘What would a man feel in the place of the woman protagonist?’ and ‘How did a stereotype limit the participants in the scenario?’ Offered the audience with a chance to reflect and grow from the workshop.

The logistics of the project was handled by Viachelsav and a 6-7 person volunteer team. The project budget received funds from an NGO supported by the United Nations General Assembly. This allowed the project to hire a team of professional actors from a theatre company. The project was also supported by the US Embassy in Bishkek.

The project concluded with 6 workshops in total. 2 workshops took place on college campuses in Kyrgyzstan, 3 more took place in Bishkek and other population centers in Kyrgyzstan, and 1 workshop was held in Kazakhstan. The international scope of the project was required by the NGO providing the funding for the project. In total, the project ran for 6 months with 2 months taken up by the workshops themselves.

General feedback from participants was very positive. They described their experiences with the workshops as ‘emotional’ and said they ‘felt touched.’ There was also positive feedback on the caliber of performers, which was made possible by the hiring of professional actors. Using the results of pre and post behavioral surveys, it was found that participants had a 58,56% increase in the ability to recognize and respond to harassment, domestic violence, and violations of women’s rights and a 18,91% increase in the confidence to initiate conversations about gender issues with friends, family, or colleagues. A common response to the project was the desire for more workshops and events.

What came after The Theatre of the Oppressed?

There is no planned direct continuation of the project. The actors and directors for the performances were professionals and would perform again for fair compensation. In fact, the director of civic engagement at AUCA used a version of the project in a college workshop by collaborating with the same theatre group on a similar subject. That workshop targeted the stereotypes faced by elderly women in Kyrgyzstan.

Viacheslav’s Experience with the Civic Engagement Course

Viacheslav noted that the course prepared him for the importance and delicate nature of working with a team. He found the lessons on how to put together a team quite helpful. By working on how to get a prospective team to be on the same page, Viacheslav was better prepared to put together the team that made his project possible. He stated that ‘shared values among the team are how to get people to want to participate.’

The “Theatre of the Oppressed” project itself was directly created through the assignments in the OSUN Civic Engagement Course. The project’s implementation process was helped by the practical elements of planning that the course required. Thus, Viachelsav felt prepared for the project from the course. For Viacheslav, the scope of the course and the importance of relationships to create camaraderie made the overall course feel rushed. “Building relationships takes time and I wanted more time for that.” Since it is more difficult to do a project with little to no budget, Viacheslav said that he wished there was more time spent on how to find sponsors and partners. He also said that he “definitely valued the practical efforts more than the theory and philosophy, as engaging as that was. I have forgotten a lot of it.”

How the Course Impacted the Theatre of the Oppressed: Teamwork and Project Management

As previously noted, the biggest impact of the Civic Engagement Course on the project for Viacheslav was how it prepared him for the teamwork required on a project of such a scale. He felt more confident managing a team. “You don’t just order people around. You are a member of the team

who happens to be directing.” He also admitted that his natural introversion made this aspect of managing difficult to navigate, but that the course helped him overcome this challenge.

Another difficulty in the project for Viachslav was reality meeting expectations. No project proposal is ever going to match the final realized project. “It happens all the time but how do you personally manage yourself against this reality?” But without that initial proposal, Viachslav acknowledges that there would not have been an expectation of what the project looked like, much less a reality that the proposal could be compared to. Viachslav is proud of the work he has done and credits the civic engagement course in setting up the eventual success that was achieved through his hard work.